Field activities in Greenland are often confined to spring and summer. In autumn and winter, low temperatures, snowfall, the lack of sunlight, and more frequent storms do not provide optimal working conditions. Besides, the most interesting processes to study primarily occur in the warm season, such as the melting of the glaciers and ice sheet.

There are two distinct peaks in Greenland field activities. The first is in spring, for those people who need to get out there when things are still frozen, but when daylight and weather conditions are workable. The second peak is in mid-to-late summer, when weather conditions are best, melting is strongest, and the ice sheet margin and tundra is snow-free and more accessible. In between there is a potentially less pleasant period with often soggy conditions, and billions of mosquitoes. With the summer peak getting underway, let’s see what the spring rush is all about.

Installing instruments before the warm season

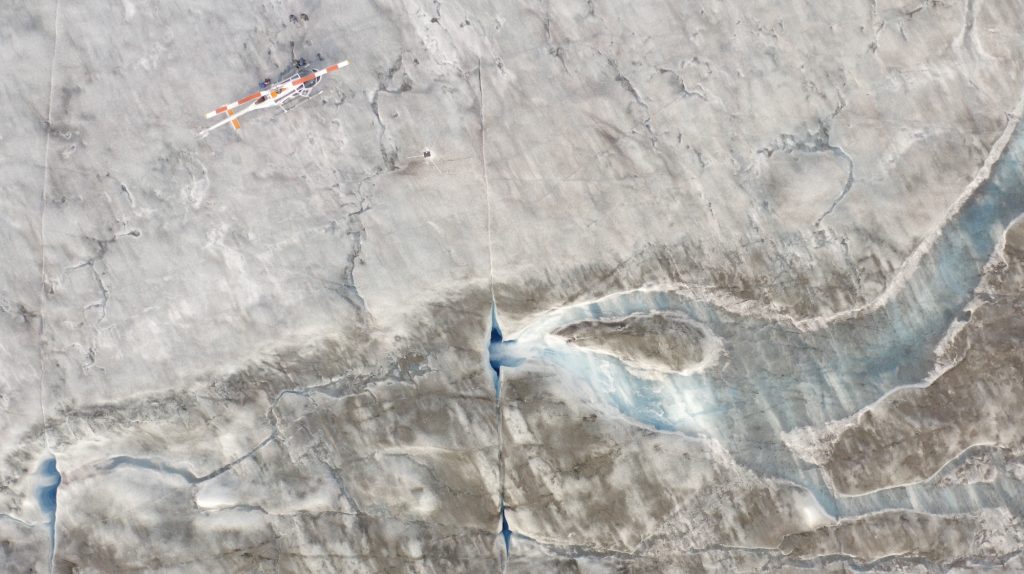

A good reason to get over to Greenland in spring is when you want your instruments in place to monitor what’s happening during the “warm” season, when plants grow, animals reproduce, and glaciers melt. Or, in the case of the University of Fribourg, when meltwater is generated at the top of the snowpack on the ice sheet. The Swiss scientists have now returned several times to the same sites in the lower accumulation area. They study how much meltwater gets refrozen in the cold snow underneath the surface, how much runs off into the ocean, and how this will change in time. Greenland Guidance provided weather forecasts for them to optimize their activities and prepare camp for storms, if needed. This spring their field team had two weeks on ice with surprisingly good weather conditions.

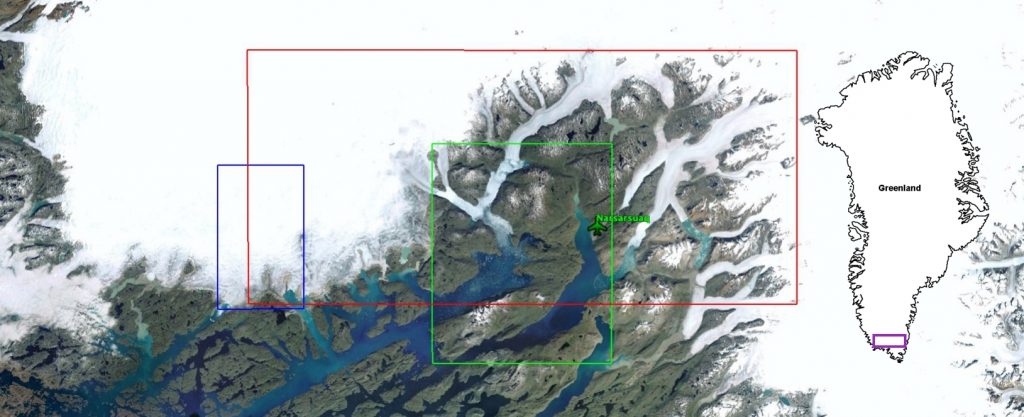

Another team out there this spring was the University of Liverpool, who where installing GG-built instruments at a fast-flowing glacier in southwest Greenland. They are investigating a glacier that has retreated a lot in the past few years. When such a glacier experiences melt, an already complex system becomes even more complicated, for instance because of large pulses of meltwater originating from ice-dammed lakes along the sides. Or from rain events. With their instruments up and running in mid-May, they timed it well.

In May and June, the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) visited GC-Net weather stations high on the ice sheet. This is part of their annual maintenance efforts that take place in spring to make sure all systems are up and running during summer. We were invited along to help out. Each station takes several hours to service, but the more people can help, the faster the Twin Otter airplane can return to town. The machine experienced engine trouble, but luckily this happened at the airport before departure, and not on or over the ice sheet.

Snow conditions

A second reason for the GC-Net maintenance to take place when it is a bit colder has to do with snow conditions. The scientists need to dig deep snow pits to asses the mass of the snow that fell since the last site visit, and this is done best before seasonal melting happens.

For others a cold snow layer means increased safety. Ski traversers crossing the ice sheet have to pass crevasse fields, and this is done much more safely if there is a solid snow bridge on top, deposited during winter. When snow gets wet because of melting, such bridges get weaker, and falling through them into a deep crevasse becomes a serious threat. That’s why the wind-powered kite-ski traverse team led by Bernice Notenboom did their expedition before the melt season, in May. They traveled an astonishing distance of nearly 2000 km from ice sheet base Dye-2 to the northwestern town of Qaanaaq. During their expedition they were confronted with several storms that we warned them about via satellite transmission.

Preparations for summer

Often spring activities are mere preparations for summer expeditions. Take for instance the greenhouse in Narsaq in south Greenland. In order for charitable organization Greenland Trees to be able to plant trees along south Greenland fjords at the end of summer, their new greenhouse had to be prepared for growing seeds and cuttings in April and May. It took a lot of effort, but is was truly nice to notice how happy locals are with the project, and how eager they are to collaborate – including schools.

In terms of volume, most of our clients and collaborators are scientists or camera crews, asking where to rent a boat, how to get permits, which locals to interview, and how to get to a remote site. But we also provided support to Swedish company SKB, who have been running and funding science projects in the Kangerlussuaq region over the past 15 years. In preparation of a groundwater sampling campaign to occur at their unique bedrock borehole in late summer, we went ahead and inspected the state of their equipment, inventoried their storage, and downloaded data collected by sensors deep underground.

With SKB discontinuing their Greenland science projects as of 2022, Greenland Guidance was selected to take over their surface hydrology project situated in the Two Boat Lake catchment. This is an exciting opportunity, and we welcome suggestions for scientific collaboration by anyone who reads this. More about the TBL project in an upcoming blog post!

Busy times

For Greenland Guidance, spring is the busiest time of year. This is when we support field parties remotely, take part in fieldwork ourselves, prepare for fieldwork in summer, and custom-build instruments for summer deployment. Nowadays we are also building and refurbishing instruments for use in the Himalayas for Utrecht University and the Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee. And we’ve expanded our area of expertise by now also focussing on ocean sciences through collaboration with MetOcean in Canada, and our new instrument platform Polar Monitoring.